Anyone with an interest in the Barbican has heard of Chamberlin Powell and Bon. They are justly renowned as the architects and designers of the Barbican estate and the Barbican Centre. But they have another claim to fame, just as important to the creation of the Barbican estate – as political operators. Somehow, they talked the project up from being just a vague idea of having housing in the City until it seemed almost inevitable. On the surface it seems as if they were merely doing the bidding of their clients, the City Corporation, by producing neutral balanced reports when requested. But that’s only how it seems on the surface. In reality they went far beyond their apparent role as servants of the Corporation patiently waiting to do the Corporation’s bidding. In fact, they manoeuvred, nudged, and persuaded the important players at every stage to keep the project growing and on track. I think there would have come a day when the City grandees, up to their necks in a huge project with burgeoning costs and endless labour problems, wondered how it had ever come about. This is how I believe it happened.

The first question is this: How did Chamberlin Powell and Bon become involved at all? In 1954 all the momentum in the City Corporation was behind a commercial scheme for the creation of a sea of office towers from London Wall northwards up to the City’s boundary with Islington. The City’s policy was the Holden Holford plan. Then came the more Barbican-specific Martin Mealand plan, which was, again, mainly commercial, with just a smattering of residential around St Giles Church. This was being promoted by the powerful Improvements and Town Planning Committee, which had control of redevelopment of the bombed areas of the City in practice.

However, there was an important group of like-minded City council members who would favour a residential development. They gathered around Eric Wilkins, the influential chairman of the Public Health Committee. It was Wilkins and his committee who had pushed through the Golden Lane estate scheme, which Chamberlin Powell and Bon were then working on.

It seems highly probable to me that it was Peter Chamberlin (known to his friends as Joe) who approached Wilkins and urged him to consider a residential development for the Barbican – which was, after all, only one street away from where they were working on the Golden Lane Estate – and to lead a fightback against the projected tower blocks all the way to Islington. Or perhaps Wilkins bent Chamberlin’s ear first. But I’m quite sure they then formed a little ‘conspiracy’ between them.

Rather surprising thing then happen. The Town Clerk, who wasn’t directly involved in any of the development issues, decided apparently out of the blue to instruct Chamberlin Powell and Bon to produce a report on the potential for housing development in the City. When I first came across this report in the City’s archives, it seemed quite a mystery. But after following the story from many angles, I imagine Mr Wilkins and Joe Chamberlin came knocking on the Town Clerk’s door and bent his ear.

Chamberlin Powell and Bon then set about writing their 1955 report to the City. What this concluded was that the Barbican site was ideal to be developed into a residential neighbourhood. They were architects, so you would expect that their arguments would be architectural. Not a bit of it. It’s really a highly political pamphlet. They knew exactly what political buttons needed to be pressed if their scheme was to have any hope of success among those councilman and aldermen of the City who were not already in the pockets of commercial developers. The essential thing they had to do – and Wilkins would have emphasised this as an accountant himself – was to convince the City grandees that any development would be profitable. There was no talk at any stage in the Barbican process of ‘the City’s gift to the country’ or any similar public-spirited motivation. The architects realised they had to demonstrate that a certain number of flats could be built, and that they could be rented to middle and upper-class financiers and professionals working in the City at rents which would make the development profitable.

So, they proposed creating flats which would serve a population at a density of 300 persons per acre – 70 persons per acre more than was then permitted by the London County Council across London. It was all about profit. Having ticked that box, they then threw in other things that the City as a local authority ought to be concerned about, such as civic amenities, schools, and open spaces. They proposed including the City of London School for Girls and the Guildhall School of Music and Drama, both of which were currently in outmoded or unsuitable premises and needed to be relocated. Of course, they also knew that they needed to make the whole thing sound exciting and attractive, so they introduced ideas like a swimming pool, squash courts, and an exhibition space which would all be housed in a sort of truncated pyramid.

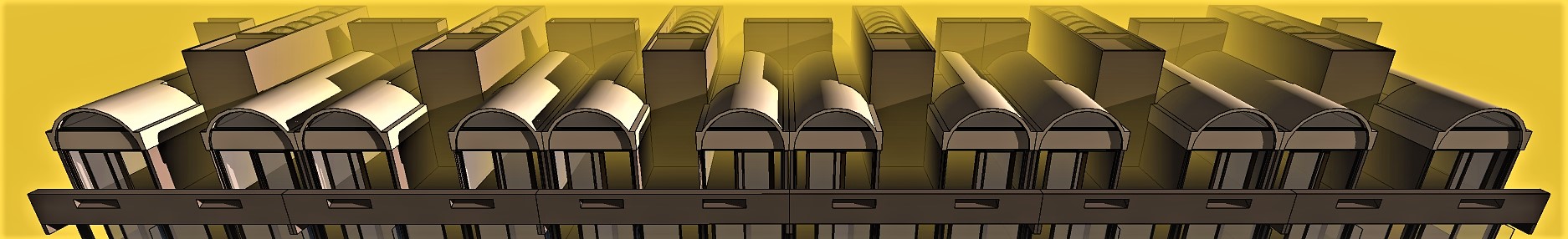

But the architecture of this scheme was not in the least bit Modernist or Brutalist. The architects took as their models the Inns of Court – Gray’s Inn, Lincoln’s Inn, and Temple – and proposed a series of interlocking courtyards of terraces. Certainly, they threw in some towers because that was only way to achieve 300 persons per acre and make the whole proposal enticing to City men used to concentrating on the bottom line.

When the report was revealed by the Town Clerk, I imagine that the Improvements and Town Planning Committee was mightily put out. They couldn’t exactly dismiss it out of hand. Instead they tried to bury it. They arranged a ‘conference’ at which the two competing schemes could be viewed, assessed, and their respective merits discussed. The two schemes were the Martin Mealand plan and Chamberlin Powell and Bon’s 1955 plan. But when the attendees arrived, they discovered that only the Martin Mealand plan was on offer. In fact, discussion of the Chamberlin Powell and Bon plan was refused, and they were told that they could only discuss residential development on 13 acres of land (which was the land allocated for some housing in the Martin Mealand plan because it was the one piece of land where no one particularly wanted to build office blocks.). If they thought this ploy was going to defeat Eric Wilkins, they had misjudged their man.

Eric Wilkins called a special meeting of the Court of Common Council and insisted on making a speech to it. The speech he made was really quite outstanding in my opinion. I still chuckle at the way he absolutely skewered the Improvements and Town Planning Committee while appearing to be praising them, or at least excusing them. This was one of his best bits.

“Naturally, my Lord Mayor, it is the Improvements and Town Planning Committee, which advises the Court on matters of planning, but it is precisely this hard-working and overworked committee which has brought down upon the Corporation and itself such a welter of public criticism. … “It is this confused, criticised and totally inadequately advised committee that is responsible for the development of the Barbican. … How does it attempt to discharge its duty? When presented in June last with the most detailed and comprehensive scheme prepared by Messrs Chamberlain Powell and Bon – whose Golden Lane scheme evoked from the eminent assessor of the Golden Lane competition that “it stands out from all the others by the assurance and imagination of its plan”, it files it in a pigeonhole.”

It is interesting to read the minutes of the Special Committee which followed. The Special Committee appears to have been some kind of roving trouble-shooter Committee which reported direct to the Court of Common Council on other committees’ activities.

The Special Committee had previously dismissed plans for housing. After Wilkins’ intervention they found themselves very much on the back foot. They distinguished their earlier decision by attributing it to a Labour minister’s refusal to approve a development in the Bridgewater estate. Now, with the wind firmly behind Wilkins and his supporters, the Special Committee found itself having to back serious consideration of the Chamberlin Powell and Bon residential scheme.

Chamberlin Powell and Bon had done something quite clever in their 1955 report. They’d only been asked to report on the viability of housing in the City, not to propose anything in any great detail. But off their own bat, they added all sorts of suggestions on what the new development would look like and what it would contain, to make it much more ‘real’.

It was not unexpected that when the Special Committee needed to push the matter forward, they recommended instructing Chamberlin Powell and Bon to produce the next, more detailed, report for consideration.

Chamberlin Powell and Bon and their proposed residential development for the Barbican had now attracted many enemies. Anthony Mealand, the chief planning officer and co-author of the competing Martin Mealand scheme might have been expected to be the most hostile. But, in fact, he was supportive. His scheme was still employed south of the Barbican. But his successor, who was now called the City Architect, was apparently implacably opposed to the residential development right from the start. Another enemy was Francis Forty, the City Engineer. He had put forward the much-derided Forty plan several years earlier on behalf of the Improvements and Town Planning Committee – some might say, on behalf of vested City interests – to simply rebuild the City as it had been before the War.

So, Chamberlin had to tread warily. The 1956 plan repeated the strategy of arguing that a residential development could be profitable. It also made sure of the support of councillors with special interests, such as members of the Schools Committee and the Music Committee. (For example, they found a way to shoehorn the City of London school (for boys) into the scheme.)

But Chamberlin had greater ambitions for the scheme than what was already proposed. He took a risk. He insisted that he would only produce the revised report if the City agreed to include in it the land between Beech Street and Fann Street. He used the need to find space for all the schools as the excuse to justify the North Barbican addition. That was agreed.

The Special Committee recommended the creation of a Barbican Committee, to take over the responsibility for redevelopment of the Barbican area from the Improvements and Town Planning Committee. Wilkins arranged to have himself appointed as chairman. This was a significant milestone on the road to gaining approval for the estate. But there were many other obstacles along the road. There was a proposal made – I assume to the Court of Common Council, but I’m not sure – for William Holford to be appointed in place of Chamberlin Powell and Bon. He was the respected co-author of the Holden Holford report which was the basis for the commercial development of the parts of the City destroyed in the war. The Improvements and Town Planning Committee no doubt hoped to use him to wrest back control for a commercial development. That failed.

Behind the scenes, Chamberlin had opened up another powerful supporter. He either already knew socially, or arranged to be introduced to, Duncan Sandys, MP, the new Minister of Housing and Local Government. He persuaded Duncan Sandys to press the case for the residential development in the Barbican area. Duncan Sandys sent several letters to the Lord Mayor supporting residential development, increasingly forceful in tone.

In 1957 he went so far as to press specifically for the Chamberlin Powell and Bon scheme to be implemented: “The Minister expressed his interest in the schemes and it is his belief that the creation of a genuine residential neighbourhood in this part of London would be of the greatest value to the proper planning of the area. … He was inclined in principle to prefer the Chamberlin Powell and Bon scheme for the Barbican area, which provided more residential accommodation and seemed to him to give a greater sense of the real residential neighbourhood.”

Chamberlin Powell and Bon were required to produce a number of additional reports after the 1956 report – the most comprehensive of these was their 1958 report – mainly to deal with issues about finance. They kept maintaining the case that it could all be afforded and would make a profit.

Finally, Chamberlin Powell and Bonn were instructed to produce their 1959 report, which was to be the most detailed and comprehensive report yet on the viability of a housing solution to the problem of what to do with the Barbican area. You might think that, by that stage, it was just a matter of coasting downhill to ultimate victory. But they still had a big problem to face. The problem was that the London County Council, which had planning oversight for the development, would not accept a density as high as 300 persons per acre, which was the basis on which Chamberlin Powell and Bon were claiming that the scheme would be viable financially. The LCC required a density of no more than 230 persons per acre. Chamberlin Powell and Bon responded in two ways. First, they increased the height of the towers and thereby squeezed more residents onto the existing plot size of the towers. Second, they added additional terrace buildings which had not been proposed in the earlier schemes.

Their masterstroke was – not exactly to ignore, but definitely to exceed – the instructions they had from the City. The City Corporation were not asking them to produce a highly-detailed scheme. But Chamberlin Powell and Bon went quite some way beyond their remit with architectural drawings of layouts and even commissioning artists’ impressions of the possible future estate, just to make the whole thing more aspirational and exciting. Also, they didn’t just provide a normal typed report, as they had done with their previous reports. Instead, they had a glossy hardback book produced, which was professionally designed and laid out, and with illustrative photographs and drawings on almost every page. This book was printed in many copies. When the City Corporation received it, they were so put out that they refused to pay for it. Chamberlin had to pay for it himself. It took quite a bit of ego-massaging to arrange for the cost finally to be reimbursed.

Finally the scheme was put to the Court of Common Council, the highest committee in the City structure, for approval or refusal. It all seems so inevitable now, looking backwards, and you might imagine that this meeting was a walkover. But it was not. In fact, the vote was lost, even though it was declared as won. It turned out after the meeting was over some of the tellers counting the votes had managed to count some of the other tellers as voters on the yes side by mistake, thus giving Eric Wilkins and Chamberlin Powell and Bon the victory. The City just covered that up out of embarrassment, and the scheme went ahead. By such hair-breadths was the Barbican estate created. At every stage, something could have gone wrong, and we could all be living in Surbiton.